When analyzing running biomechanics, one critical factor that often comes under scrutiny is pelvic drop. Understanding pelvic drop is essential for identifying inefficiencies in running form, diagnosing potential injury risks, and improving overall athletic performance. This blog post delves into what is pelvic drop, how it is calculated and why the variable is important in biomechanical analysis.

What is Pelvic Drop?

Pelvic drop, also known as contralateral pelvic drop, refers to the downward tilt of the pelvis on the side opposite to the weight-bearing leg during the stance phase of running. In simpler terms, when one foot is in contact with the ground, the pelvis should ideally remain relatively balanced. However, in some cases, the opposite side of the pelvis dips lower than expected, indicating a pelvic drop.

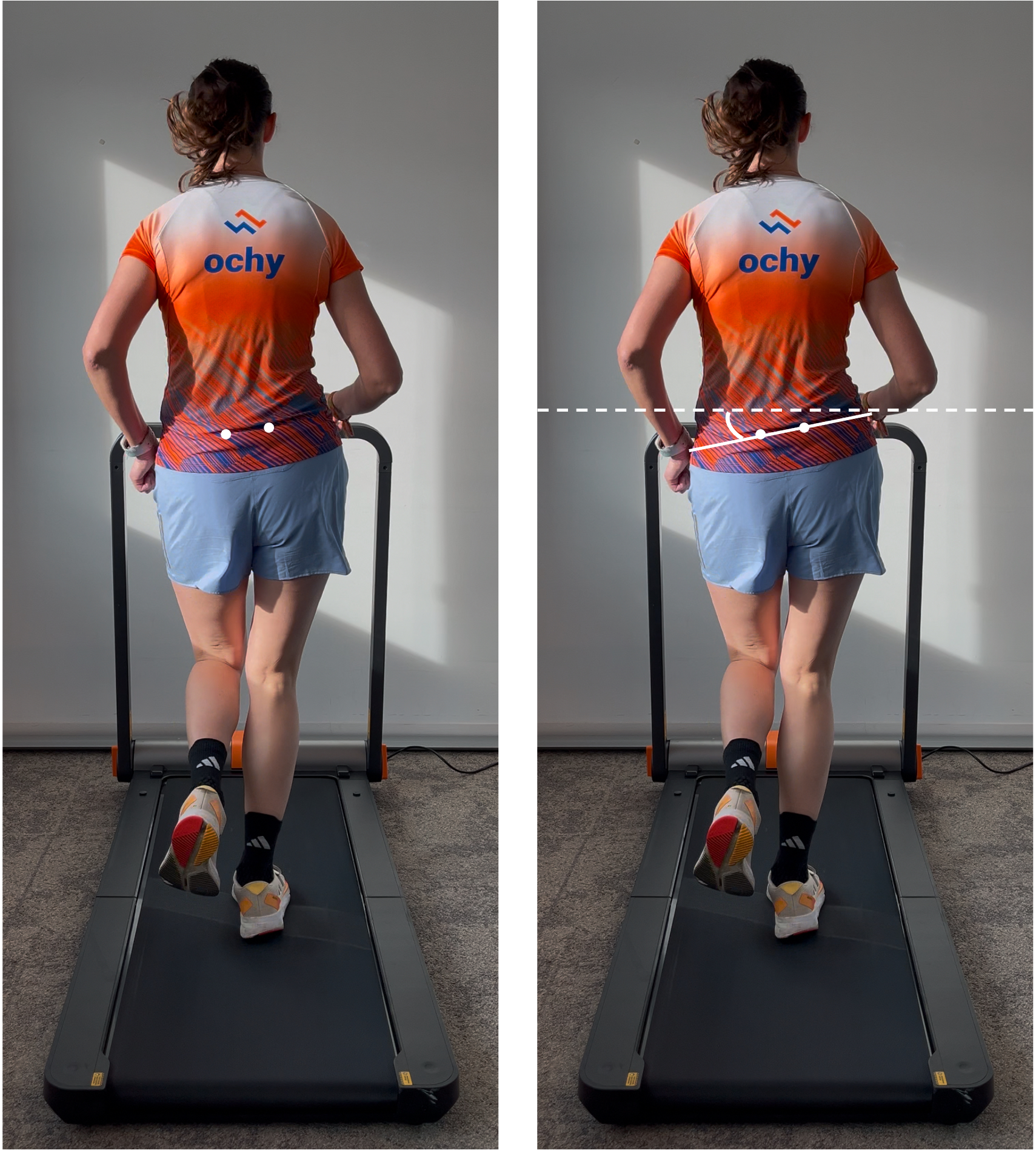

Figure 1: Visualisation of pelvic drop from a posterior view

Why is Pelvic Drop Important?

“For each 1° increase in pelvic drop, the odds of being classified as injured rose by 80%” (Bramah et al., 2018).

1. Indicator of Muscular Weakness:

Pelvic drop often signals weakness of the hip abductors (Hannigan, 2014), like the gluteus muscles. These muscles are critical for stabilizing the pelvis during single-leg activities like running (Burnet and Pidcoe, 2009; Preece et al., 2019).

2. Injury Risk Assessment:

Excessive pelvic drop can increase the stress on the lower back, hips, knees, and even the ankles. It can contribute to injuries such as iliotibial band syndrome (Fredericson et al., 2000), patellofemoral pain syndrome (Souza & Powers, 2009; Willy et al. 2012), achilles tendinopathy (Bramah et al., 2018) and lower back pain (Kendall et al. 2010).

3. Performance Efficiency:

A stable pelvis contributes to better energy transfer and running efficiency. Unnecessary movement, like a pronounced pelvic drop, leads to wasted energy and reduced performance (Schache et al., 2001).

Discussion in the Scientific Literature

Pelvic drop remains a debated topic in the scientific literature. Some studies (Hannigan, 2014; Frederisco et al., 2000, Bramah et al., 2018) suggest that strengthening key muscles can reduce pelvic drop, alleviate pain and reduce the risk of injuries. However, others (Burnet, 2008; Burnet and Pidcoe, 2009; Kendall et al., 2010) think that a more comprehensive biomechanical approach should be considered to improve runners' posture. This highlights the need to analyze pelvic drop within a broader biomechanical framework. The body may use pelvic drop as a compensatory strategy in response to misalignment elsewhere in the kinetic chain, whether in the upper or lower body. Thus, assessing pelvic drop in isolation may overlook other contributing factors in a runner’s posture.

How is Pelvic Drop Measured?

From a biomechanical perspective, pelvic drop is quantified by measuring the angle formed between a line drawn through the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) and the true horizontal reference line (Pipkin et al., 2016).

To be able to record the pelvic drop angle, you can:

- Use motion capture with markers placed at the PSIS level. Motion capture is precise but costly and typically available only in specialized biomechanics laboratories.

.png)

Figure 2: 2D representation of contralateral pelvic drop at midstance using motion capture. (A) injured runner; (B) healthy runner (Bramah et al. 2018)

- Use video analysis tools like Ochy, where the runner is recorded from a back view on a treadmill during running. A simple phone is all you need to record yourself and get a quick analysis.

Figure 3: 2D representation of contralateral pelvic drop at midstance using Ochy

How can I prevent from injuries?

1. Identify your posture:

The first step is to know if you have a pelvic drop by undergoing a biomechanical analysis.

- Keep it in mind during training:

Imagine a string pulling the top of your head upward, helping to keep your pelvis level and stable as you run. Focus on controlled landings—avoid "crashing" onto your leg when your foot contacts the ground.

- Strength Training:

Pelvic drop have been associated with weakness in hip abductors (Frederisco et al.,2000; Hannigan, 2014). Strengthen your gluteal muscles, hamstrings, adductors, and hip flexors to enhance pelvic stability. Exercises like single-leg squats, clamshells, hip thrusts, and side-lying leg lifts are particularly effective.

.png)

Figure 4: Side-lying leg lifts: example of strength training to avoid pelvic drop

4. Flexibility and Mobility:

Incorporate stretching routines to maintain flexibility in the hip flexors, hamstrings, and lower back muscles. This balance of strength and flexibility supports optimal pelvic control.

.png)

Figure 5: Example of hip muscles stretching

5. Neuromuscular Training:

Practice exercises that improve balance and proprioception, such as single-leg stands or dynamic stability drills, to enhance neuromuscular control during running.

.png)

Figure 6: Example of neuromuscular training as proprioception

Find more examples of strength training exercises on the Ochy app!

Conclusion

Monitoring pelvic drop is a fundamental aspect of biomechanical analysis in runners. While excessive pelvic drop has been linked to muscular weaknesses and increased injury risk, its role remains debated in the scientific literature. Some research suggests strengthening key muscles can mitigate its effects, while other studies indicate that a more global biomechanical approach should be consider to correct the runners' posture. Therefore, it is important for runners to determine whether they have a pelvic drop; however, this should not be assessed in isolation. Instead, pelvic drop must be considered within the larger context of overall biomechanics, as other parts of the body, such as the upper and lower kinetic chain, may influence its presence. Runners, coaches, and clinicians should adopt a global approach when analyzing and addressing pelvic mechanics. By considering all contributing factors, runners can optimize performance and reduce injury risk.

Download Ochy now to analyze your running posture.: https://app.ochy.io/

References

- Bramah, Christopher, Stephen J. Preece, Niamh Gill, and Lee Herrington. 2018. ‘Is There a Pathological Gait Associated With Common Soft Tissue Running Injuries?’ The American Journal of Sports Medicine 46 (12): 3023–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518793657.

- Burnet, Evie. 2008. ‘Frontal Plane Pelvic Drop in Runners: Causes and Clinical Implications’. Theses and Dissertations, January. https://doi.org/10.25772/BRSC-TP68.

- Burnet, Evie N., and Peter E. Pidcoe. 2009. ‘Isometric Gluteus Medius Muscle Torque and Frontal Plane Pelvic Motion during Running’. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 8 (2): 284–88.

- Fredericson, Cookingham, Chaudhari, Dowdell, Oestreicher, and Sahrmann. 2000. ‘Hip Abductor Weakness in Distance Runners with Iliotibial Band Syndrome’. ResearchGate, October. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042752-200007000-00004.

- Hannigan, James. 2014. ‘The Relationship Between Hip Strength and Hip, Pelvis, and Trunk Kinematics in Healthy Runners’, September. https://hdl.handle.net/1794/18317.

- Kendall, Karen D., Christie Schmidt, and Reed Ferber. 2010. ‘The Relationship Between Hip-Abductor Strength and the Magnitude of Pelvic Drop in Patients With Low Back Pain’, November. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.19.4.422.

- Pipkin, Andrew, Kristy Kotecki, Scott Hetzel, and Bryan Heiderscheit. 2016. ‘Reliability of a Qualitative Video Analysis for Running’. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 46 (7): 556–61. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.6280.

- Preece, Elsais, Jones, and Herrington. 2019. ‘Abnormal Muscle Coordination Rather than Hip Abductor Muscle Weekness May Underlie Increased Pelvic Drop during Running’. In ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336284814_ABNORMAL_MUSCLE_COORDINATION_RATHER_THAN_HIP_ABDUCTOR_MUSCLE_WEAKNESS_MAY_UNDERLIE_INCREASED_PELVIC_DROP_DURING_RUNNING.

- Schache, Anthony G., Peter D. Blanch, David A. Rath, Tim V. Wrigley, Roland Starr, and Kim L. Bennell. 2001. ‘A Comparison of Overground and Treadmill Running for Measuring the Three-Dimensional Kinematics of the Lumbo–Pelvic–Hip Complex’. Clinical Biomechanics 16 (8): 667–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(01)00061-4.

- Souza, Richard B., and Christopher M. Powers. 2009. ‘Differences in Hip Kinematics, Muscle Strength, and Muscle Activation Between Subjects With and Without Patellofemoral Pain’. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 39 (1): 12–19. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2009.2885.

- Willy, Richard W., Kurt T. Manal, Erik E. Witvrouw, and Irene S. Davis. 2012. ‘Are Mechanics Different between Male and Female Runners with Patellofemoral Pain?’ Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 44 (11): 2165–71. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182629215.